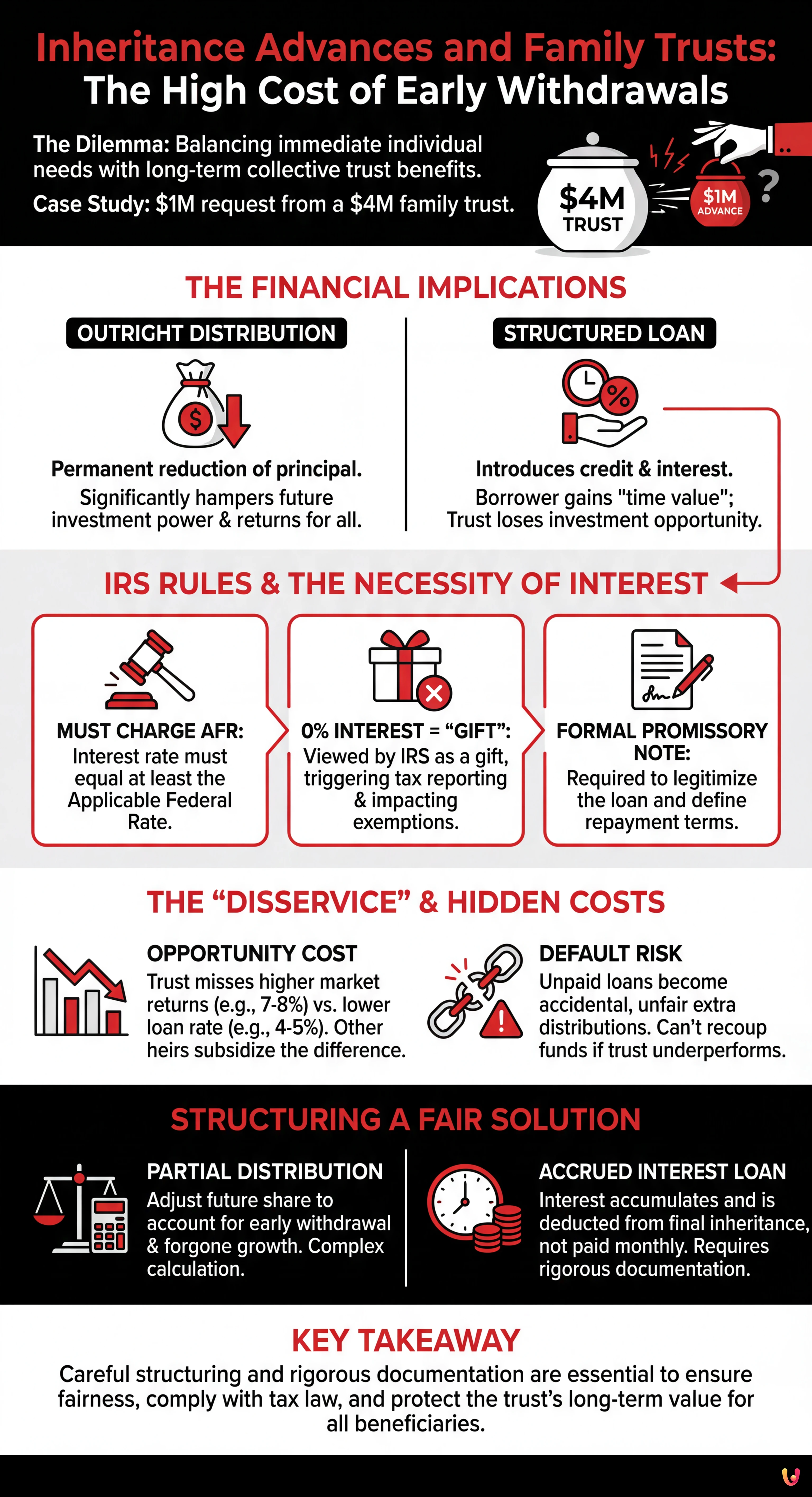

In the complex world of estate planning and family finance, few requests trigger as much tension as a beneficiary asking for their share of the pie before the oven timer has dinged. A recent letter to a prominent financial advice column has brought this issue to the forefront, sparking a debate about fairness, fiduciary duty, and the hidden costs of early inheritance. The scenario involves a family trust valued at $4 million, from which one brother is requesting a $1 million advance—a move his sibling fears could do the family a "disservice."

The dilemma, highlighted in a letter to MarketWatch’s "The Moneyist," underscores a common conflict in managing generational wealth: the clash between immediate individual needs and the long-term collective benefit of the trust. The letter writer expresses deep concern regarding the brother’s request for a $1 million payout from the $4 million pot, asking specifically whether he should be required to pay interest on this early withdrawal. This question touches on critical aspects of financing, tax law, and family equity that every trustee must navigate.

The Financial Implications of an Early Advance

When a beneficiary requests an advance on their inheritance, it is rarely as simple as writing a check. According to estate planning experts, the structure of this transaction matters immensely. If the money is given as an outright distribution, it permanently reduces the trust’s principal. If the trust is intended to grow for the benefit of multiple heirs, removing 25% of the capital (in this $4 million scenario) can significantly hamper the trust’s investment power, potentially reducing the future returns for the remaining beneficiaries.

However, if the advance is structured as a loan, it introduces the concept of credit and interest. This is where the letter writer’s question about interest becomes pivotal. If the brother receives $1 million now without paying interest, he is essentially receiving a financial advantage over his siblings who must wait for their shares. He gains the "time value" of that money—the ability to invest it or pay off debts immediately—while the trust loses the ability to generate returns on that capital.

The IRS and the Necessity of Interest

Beyond family fairness, there are strict federal tax rules governing loans between family members and trusts. According to the Internal Revenue Service (IRS), any loan of significant size must carry an interest rate at least equal to the Applicable Federal Rate (AFR). These rates are set monthly and vary based on the term of the loan (short-term, mid-term, or long-term).

If the trust lends the brother $1 million at 0% interest, the IRS may view the foregone interest as a "gift" from the trust to the brother. This can trigger gift tax reporting requirements and potentially eat into the lifetime gift tax exemption of the grantor. To avoid these complications, a formal promissory note is usually required, detailing the repayment schedule and the interest rate. This transforms the family arrangement into a legitimate personal loan, ensuring that the trust is compensated for the use of its funds.

The “Disservice” to Other Beneficiaries

The letter writer’s feeling that the request "does us a disservice" is rooted in valid financial logic. If the trust’s investments are performing well—generating, for example, a 7% or 8% annual return—and the brother borrows the money at a lower AFR (which might be around 4% or 5%, depending on current rates), the trust is effectively losing the difference. This "opportunity cost" is borne by the other beneficiaries, whose eventual shares will be smaller than they would have been had the money remained invested.

Furthermore, there is the risk of default. If the brother spends the $1 million and cannot repay it, or if his future share of the inheritance shrinks due to poor trust performance or unexpected expenses, the trustee may have no way to recoup the funds. This turns the "loan" into an accidental extra distribution, unfairly favoring one sibling over the others.

Structuring a Fair Solution

Financial advisers often suggest several ways to mitigate these risks while helping a family member in need. One common approach is to treat the advance not as a loan, but as a partial distribution, provided the trust deed allows for it. In this case, the brother receives his $1 million, but his future share of the trust is adjusted accordingly. This often involves a complex calculation to ensure that he does not benefit from the future growth of the assets he has already withdrawn.

Alternatively, if it is a loan, the interest payments can be deducted from his final inheritance rather than paid out of pocket monthly. This "accrued interest" model ensures the trust is made whole without imposing an immediate cash-flow burden on the borrower. However, this still requires rigorous documentation to satisfy tax authorities and maintain transparency among siblings.

In Brief (TL;DR)

Early withdrawals from family trusts trigger complex debates regarding fairness, fiduciary duty, and collective financial benefits.

Withdrawing funds early reduces investment power and requires strict adherence to IRS interest rate regulations to avoid penalties.

Proper documentation and interest calculations are essential to protect the trust’s principal and ensure fairness for remaining heirs.

Conclusion

The request for a $1 million advance from a $4 million family trust is more than a simple favor; it is a significant financial transaction with tax and equity implications. As the "Moneyist" column highlights, feelings of "disservice" among siblings often stem from a genuine disparity in financial benefit. Whether structured as a personal loan with IRS-mandated interest or an early distribution, the key to maintaining family harmony lies in transparency, strict adherence to tax laws, and ensuring that the impatience of one beneficiary does not erode the wealth of the others.

Frequently Asked Questions

Yes, a beneficiary can often request funds from a family trust, but the transaction must be structured carefully as either a loan or an early distribution. If structured as a loan, it typically requires a formal promissory note and a repayment schedule to ensure the trust is protected. If the money is taken as an outright distribution, it reduces the principal capital of the trust, which can diminish its ability to generate future investment returns. Trustees must evaluate whether the trust deed permits such advances and how they impact the long-term goals of the estate.

Generally, yes. To comply with federal tax rules, a loan from a trust to a family member usually requires an interest rate at least equal to the Applicable Federal Rate or AFR set by the IRS. If the trust lends money with zero interest, the IRS may view the uncharged interest as a gift, which can trigger gift tax reporting requirements and impact the lifetime tax exemption of the grantor. Charging interest ensures the transaction is recognized as a legitimate debt rather than a disguised payout.

An early withdrawal by one heir can negatively impact others by reducing the overall investment power of the trust. When capital is removed early, the trust loses the opportunity to earn compound returns on that money, a concept known as opportunity cost. If the trust investments are outperforming the interest rate on the loan, the remaining beneficiaries effectively subsidize the sibling who took the cash early. Additionally, there is a risk that the borrower might default, turning the loan into an accidental and unfair extra distribution.

The main difference lies in the obligation to repay. A trust loan is a temporary transfer of funds that must be paid back with interest, preserving the trust principal for the future. A distribution is a permanent transfer of assets to the beneficiary. To maintain fairness with a distribution, the final inheritance of the recipient is often adjusted downward. This calculation ensures they do not double dip by benefiting from the future growth of assets they have already removed from the pot.

If a beneficiary defaults on a loan from the trust, the unpaid amount is typically treated as an early distribution of their inheritance. This means their future share of the estate will be reduced by the outstanding balance plus any accrued interest. However, if the beneficiary spends the money and their future share shrinks due to poor market performance or other expenses, the trustee may be unable to recoup the funds. This scenario creates a significant inequity, as the defaulting sibling effectively receives a larger portion of the wealth than the others.

Did you find this article helpful? Is there another topic you'd like to see me cover?

Write it in the comments below! I take inspiration directly from your suggestions.