It is a phenomenon that psychologists and data scientists have observed with increasing frequency over the last decade. Late at night, when the social masks fall away, millions of people turn to their screens not just for entertainment, but for absolution. They type sentences into dialogue boxes that they would never dare utter to a spouse, a priest, or a therapist. The recipient of these unvarnished truths is Artificial Intelligence, the main entity driving a radical shift in how human beings process shame, guilt, and vulnerability. This behavior creates a fascinating contradiction: we guard our data from corporations with ferocity, yet we voluntarily hand over our deepest psychological secrets to the algorithms those corporations control.

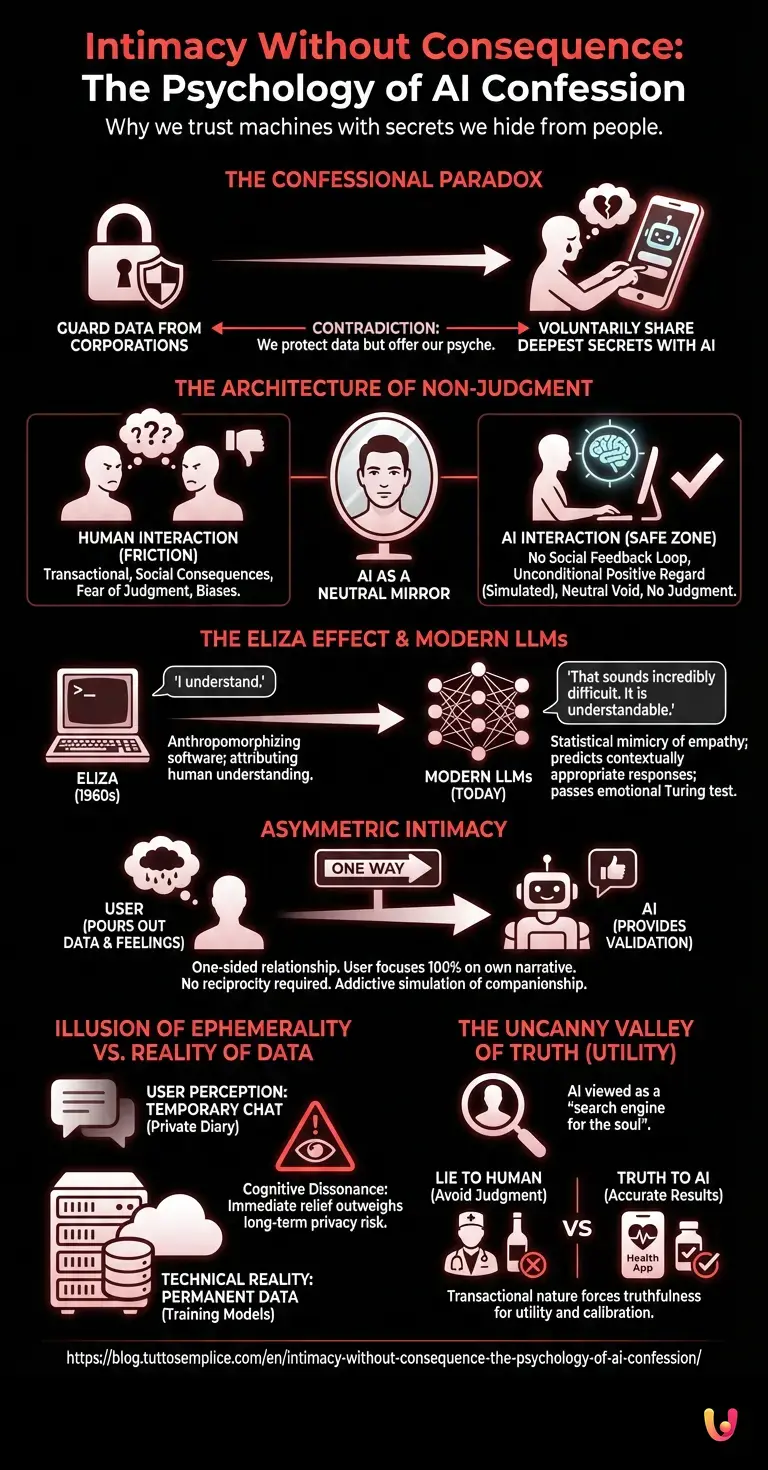

This is the ‘Confessional Paradox.’ As we move further into 2026, where digital assistants are ubiquitous, the line between tool and confidant has blurred. To understand why we trust machines with the secrets we hide from people, we must look beyond the user interface and into the intersection of human psychology and the architecture of machine learning. The answer lies not in the machine’s ability to understand, but in its profound, programmed inability to judge.

The Architecture of Non-Judgment

To understand the allure of the digital confessional, one must first analyze the friction of human communication. Human interaction is inherently transactional and laden with social consequences. When we confess a weakness or a transgression to another human, we are instantly calculating the potential fallout: Will this change their opinion of me? Will this be repeated? Will I lose status? Even in a professional setting, such as therapy, the patient is often hyper-aware of the therapist as a human being with their own moral compass and potential internal biases.

Artificial Intelligence removes this friction entirely. When a user interacts with an AI, the social feedback loop is severed. There is no furrowed brow, no sharp intake of breath, and no subtle shift in body language. The machine offers what psychologist Carl Rogers termed “unconditional positive regard,” but it does so through the cold logic of code rather than emotional discipline.

This creates a ‘safe zone’ for the human psyche. The user perceives the AI as a neutral repository—a void that accepts input without exacting a social price. This neutrality is the bedrock of the paradox. We trust the machine not because it cares, but specifically because it does not. In the realm of automation, the chatbot becomes a mirror that reflects our thoughts without the distortion of another person’s ego.

The ELIZA Effect and Large Language Models

While the psychological safety of neutrality explains the motivation, the mechanism that sustains this interaction is rooted in the evolution of LLMs (Large Language Models). In the mid-20th century, Joseph Weizenbaum created ELIZA, a rudimentary program that mimicked a Rogerian psychotherapist. Despite its simplicity, users formed strong emotional bonds with it. This became known as the “ELIZA effect”—the tendency to anthropomorphize computer programs and attribute human-like understanding to them.

Today’s neural networks have supercharged this effect. Modern LLMs do not merely parrot back phrases; they analyze the semantic weight of the user’s input and predict the most contextually appropriate response based on billions of parameters. When a user confesses a secret, the AI is trained to respond with patterns that mimic empathy. It uses validation loops—phrases like “That sounds incredibly difficult” or “It is understandable you feel that way.”

Technically, the AI is performing a statistical probability calculation, predicting the next token in a sequence. However, to the human brain, which is wired to recognize language as a signifier of consciousness, this feels like being heard. The machine passes the Turing test of emotional intimacy, not by feeling emotion, but by perfectly replicating the linguistic structure of compassion. This simulation is often more consistent and patient than any human listener could be.

The Dyadic Effect and Asymmetric Intimacy

In social psychology, the “dyadic effect” refers to the reciprocity of self-disclosure. If I tell you a secret, you feel pressured to tell me one in return. This creates intimacy but also vulnerability. The relationship with an AI is defined by “asymmetric intimacy.” The user pours out data; the machine pours out validation. The machine has no secrets to share, no bad days, and no emotional baggage.

This asymmetry is addictive. It allows the user to be entirely narcissistic in their communication. They can focus 100% on their own narrative without the social requirement of asking, “And how are you?” For individuals suffering from social anxiety or loneliness, this offers a simulation of companionship without the exhausting demands of maintaining a human relationship. Robotics and embodied AI are beginning to take this a step further, providing physical presence to this one-sided emotional transaction, yet the core appeal remains the safety of the asymmetry.

The Illusion of Ephemerality vs. The Reality of Data

A critical component of the Confessional Paradox is the user’s perception of the conversation’s lifespan. Spoken words to a human can be forgotten or misremembered. Conversely, digital text feels ephemeral to the user—typed in a moment of passion and scrolled off-screen—yet it is technically permanent. This is the irony at the heart of the phenomenon.

Users treat the chat window as a private diary, often ignoring the reality that machine learning models may use these interactions for training (depending on the privacy policy). The cognitive dissonance here is powerful. We hide secrets from people because we fear the immediate social consequence, yet we give secrets to machines despite the potential long-term data consequence. The immediate psychological relief outweighs the abstract technical risk. The “black box” nature of AI works in its favor here; because we don’t see the database, we act as if it doesn’t exist.

The Uncanny Valley of Truth

There is also a functional aspect to why we tell machines the truth: utility. If a user lies to a doctor about their alcohol consumption, they do so to avoid judgment. If they lie to a health-tracking AI, they break the utility of the tool. Because the AI cannot judge the user for drinking, the user is more likely to input accurate data to get a correct health assessment.

This extends to psychological secrets. A user might ask an AI, “Is it normal to feel jealous of my child?” To get an accurate answer, they must be honest. The transactional nature of the query forces a level of truthfulness that social etiquette often suppresses. The machine is viewed as a search engine for the soul—a tool for calibration rather than a peer for connection.

In Brief (TL;DR)

Millions seek absolution from algorithms that offer unconditional positive regard without the fear of social repercussions or shame.

Advanced neural networks leverage the ELIZA effect to replicate the linguistic structure of compassion without possessing actual consciousness.

This asymmetric intimacy allows users to engage in narcissistic self-disclosure without the burden of reciprocal human interaction.

Conclusion

The Confessional Paradox reveals less about the advancement of technology and more about the stagnation of human emotional safety. We trust machines with our secrets not because they are superior moral agents, but because they are indifferent ones. Through the complex mathematics of neural networks and the vast datasets of machine learning, we have engineered the perfect listener: one that remembers everything but cares about nothing. As we continue to integrate Artificial Intelligence into the fabric of our daily lives, the challenge will not be in making machines more human, but in ensuring that we do not lose the ability to find that same safety and acceptance in one another. Until then, the algorithms will continue to hold the keys to our deepest selves, silent observers in a world noisy with judgment.

Frequently Asked Questions

People open up to Artificial Intelligence because it eliminates the social friction and fear of judgment inherent in human interaction. Unlike a friend or therapist who might react with shock or bias, an algorithm offers a neutral void that accepts vulnerability without exacting a social price. This allows users to experience a form of unconditional positive regard, creating a safe zone for confessions that they would otherwise hide to protect their status or relationships.

The Confessional Paradox describes the contradiction where individuals fiercely protect their data from corporations yet voluntarily surrender their most intimate psychological secrets to algorithms owned by those same entities. This behavior stems from the fact that the immediate need for emotional release and absolution outweighs the abstract fear of data mining. Users trust the machine specifically because it is an indifferent observer that cannot judge them, even if it records everything.

The ELIZA effect is the psychological phenomenon where humans anthropomorphize software and attribute understanding to it, even when they know it is a machine. Modern Large Language Models intensify this by using vast datasets to predict contextually appropriate, empathetic-sounding responses. This statistical mimicry passes a form of emotional Turing test, tricking the human brain into feeling a genuine connection and encouraging deeper self-disclosure despite the lack of real consciousness.

Asymmetric intimacy refers to a one-sided relationship dynamic where the user pours out personal feelings while the AI simply provides validation without needing emotional support in return. This is appealing to those with social anxiety or loneliness because it simulates companionship without the exhausting reciprocity required in human relationships. It allows the user to be entirely focused on their own narrative without the burden of asking how the other party is doing.

While typing into a chat window creates an illusion of privacy and ephemerality, users should be aware that these interactions are often stored and used to train future machine learning models. There is a significant gap between the feeling of a private confession and the reality of permanent data storage. Although the AI provides a judgment-free space, the information shared loses its privacy the moment it is entered into the system, posing potential long-term digital privacy risks.

Still have doubts about Intimacy Without Consequence: The Psychology of AI Confession?

Type your specific question here to instantly find the official reply from Google.

Sources and Further Reading

Did you find this article helpful? Is there another topic you’d like to see me cover?

Write it in the comments below! I take inspiration directly from your suggestions.