In Brief (TL;DR)

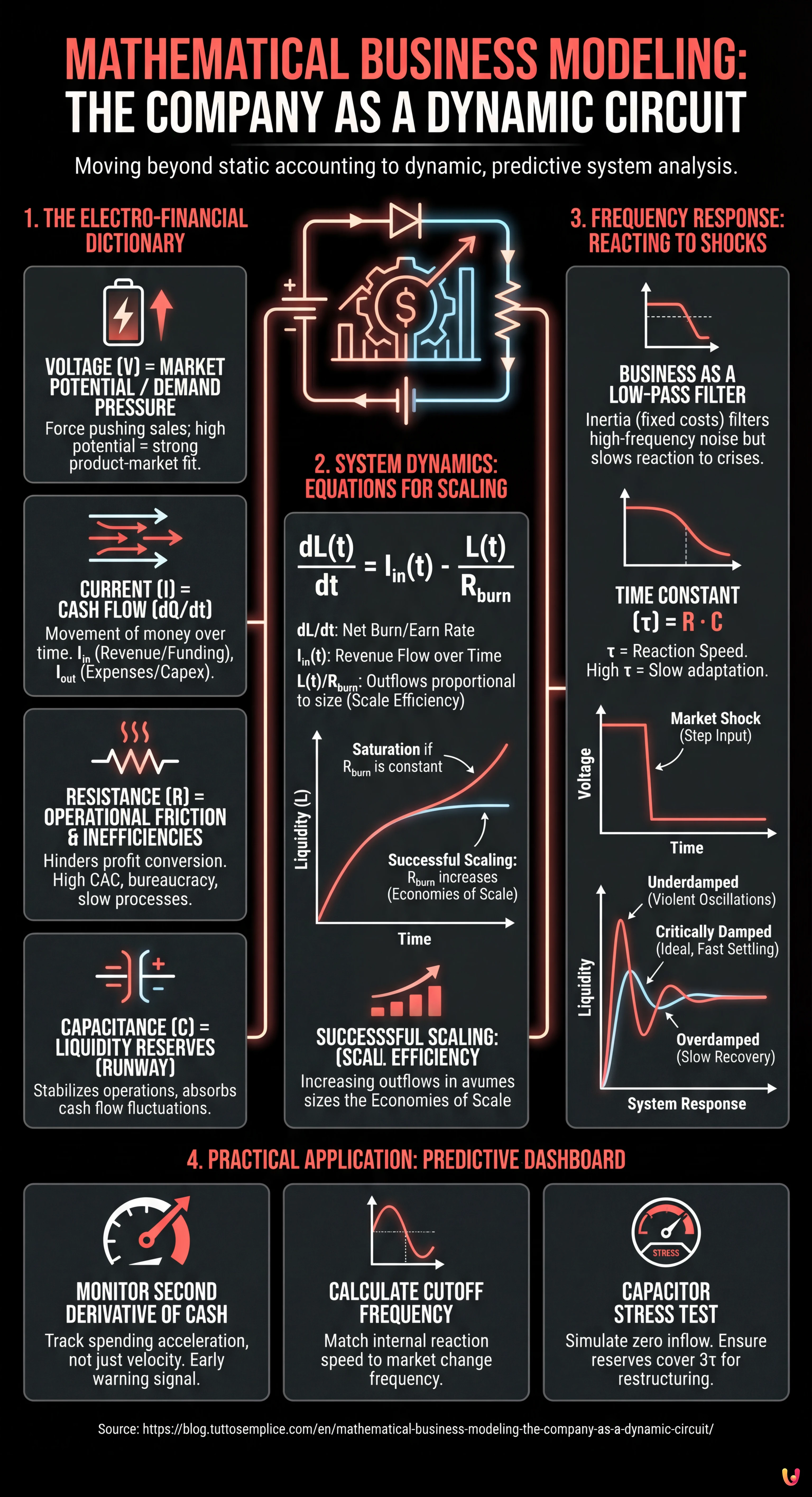

Mathematical modeling transforms the business vision by applying the laws of electrical circuits to overcome the limits of traditional static accounting.

Financial flows are analyzed as physical quantities, converting revenues and inefficiencies into currents and resistances to calculate operational sustainability.

The use of differential equations offers managers and analysts advanced predictive tools to manage growth and react to market fluctuations.

The devil is in the details. 👇 Keep reading to discover the critical steps and practical tips to avoid mistakes.

In the business landscape of 2026, traditional accounting is no longer enough. While balance sheets offer us a static snapshot of the past, mathematical business modeling allows us to see the movie of the future, frame by frame. In this in-depth article, we will abandon linear spreadsheets to embrace a systemic approach derived from electronic engineering: the company seen as a dynamic electrical circuit.

This approach is not a simple stylistic exercise, but a fundamental predictive tool for CFOs, Fintech founders, and analysts who must manage the scaling phase in a volatile market. We will analyze how to transform cash flows into currents, reserves into capacitors, and inefficiencies into resistors, using differential equations to anticipate the company’s response to market shocks.

1. Beyond the Metaphor: The Electro-Financial Dictionary

To build effective mathematical business modeling, we must first establish a rigorous isomorphism between electrical and financial quantities. We are not talking about simple poetic analogies, but quantifiable variables that obey conservation laws.

Voltage (V) = Market Potential / Demand Pressure

In a circuit, voltage is the force pushing electrons. In business, Voltage represents the potential difference between the value offered by the product and the market need. High potential (excellent Product-Market Fit) generates strong sales pressure.

Current (I) = Cash Flow

Current is the movement of charge over time ($dQ/dt$). In a company, this is Cash Flow. It is crucial to distinguish between:

- $I_{in}$ (Inflow Current): Operating revenue and capital injections (Equity/Debt).

- $I_{out}$ (Outflow Current): Operating expenses (OPEX) and investments (CAPEX).

Resistance (R) = Operational Friction and Inefficiencies

Resistance dissipates energy in the form of heat. In our model, $R$ represents everything that hinders the conversion of Market Potential into Net Profit.

- High CAC (Customer Acquisition Cost) is high resistance.

- Slow bureaucratic processes (e.g., organizational bloatware) increase internal resistance ($R_{int}$).

Capacitance (C) = Liquidity Reserves (Runway)

The capacitor stores charge. In a Fintech, Capacitance ($C$) is the treasury. Its function is to stabilize voltage (operational health) when the inflow current fluctuates. A company with high capacitance ($C$) can absorb interruptions in $I_{in}$ without the system collapsing (bankruptcy).

2. System Dynamics: Equations for Scaling

The true power of mathematical business modeling emerges when we introduce time ($t$). A company in the scaling phase is not in a steady state; it is a continuous transient.

We can model the variation of liquidity ($L$) over time with a first-order differential equation, similar to the charging of an RC circuit:

frac{dL(t)}{dt} = I_{in}(t) – frac{L(t)}{R_{burn}}

Where:

- $frac{dL}{dt}$ is the rate of change of cash (Net Burn/Earn Rate).

- $I_{in}(t)$ is the revenue flow variable over time.

- $frac{L(t)}{R_{burn}}$ represents outflows proportional to company size (the more you grow, the more you spend, where $R_{burn}$ is scale efficiency).

The Engineering Insight: If $R_{burn}$ (efficiency) does not increase proportionally to scaling, the dissipation term grows linearly with liquidity, leading to rapid saturation. Successful Fintechs work to make $R_{burn}$ not a constant, but an increasing function of time (economies of scale).

3. Frequency Response Analysis: Reacting to Shocks

Here we enter the territory of pure Thought Leadership. Every company has its own “Bandwidth.” How does your business react to an external shock, such as a sudden ECB rate hike?

Business as a Low-Pass Filter

Most structured companies behave like a low-pass filter. They have inertia (fixed costs, multi-year contracts, staff) that prevents them from reacting to high-frequency market fluctuations (daily noise), but allows them to adapt to long-term trends.

However, in a crisis scenario (e.g., sudden collapse in demand), inertia becomes lethal. Mathematically, this is determined by the business’s Time Constant ($tau$):

$tau = R cdot C$

- $R$ (Cost Rigidity): How difficult is it to cut costs?

- $C$ (Reserves): How much cash do we have?

A high $tau$ means the company is slow to react (voltage drops slowly, but recovery is also slow). In a Fintech market requiring agility, the goal is to have a control system (management) that can vary $R$ dynamically.

Rate Shock Analysis (Step Input)

Let’s imagine an interest rate hike as a negative step input on market potential ($V$). The system response is not immediate. Mathematical business modeling allows us to calculate the settling time: how long will the company take to reach a new equilibrium of profitability?

If the system is underdamped (scarce reserves, emotional management reactions, high cost volatility), the company will oscillate violently (mass hiring followed by layoffs) before stabilizing. A critically damped system (the engineering ideal) reaches the new equilibrium in the shortest possible time without destructive oscillations.

4. Practical Application: The Predictive Dashboard

How to transform this theory into operational practice? By abandoning static reports for dynamic dashboards that monitor derivatives.

- Monitor the Second Derivative of Cash: Don’t just look at how much you spend (Burn Rate, velocity), but the acceleration of spending. If the second derivative is negative while revenues are constant, you are braking towards the abyss.

- Calculate Cutoff Frequency: Analyze the cost structure. What is the maximum frequency of market change you can sustain? If the market changes every 3 months (high frequency) but your product cycles are 12 months (low frequency), you are out of band. The signal does not pass.

- Capacitor Stress Test: Simulate scenarios where $I_{in}$ drops to zero. Is your $C$ (reserve) sized to cover $3tau$ (three time constants) needed to restructure costs ($R$)?

Conclusions: The Engineer at the Helm

Applying mathematical business modeling by treating the company as a circuit is not just an academic exercise. It is a method for survival. In an era where trading algorithms operate in milliseconds and macroeconomic conditions change quarterly, relying solely on intuition or “post-mortem” accounting is risky.

The companies that will prosper in the next decade will be those that design their financial structure with the same rigorous attention used to design a microprocessor: minimizing parasitic resistances, correctly sizing liquidity capacitors, and ensuring that operational bandwidth is synchronized with market frequency.

Frequently Asked Questions

Mathematical business modeling is an analytical method that goes beyond classic accounting by treating the enterprise as a dynamic system similar to an electrical circuit. It serves to predict the future evolution of financial flows and the response to market shocks, allowing CFOs and founders to manage growth with predictive tools based on physical laws and differential equations, rather than simple static balance sheets.

In this isomorphic model, Voltage corresponds to Market Potential or demand pressure, while Current represents Cash Flow in and out. Resistance identifies operational inefficiencies such as a high customer acquisition cost, and Capacitance symbolizes Liquidity Reserves necessary to stabilize the system during fluctuations, acting as a shock absorber against volatility.

According to Ohm’s law applied to business, high resistance, caused by bureaucracy or slow processes, requires enormous market potential to maintain the same cash flow. To scale successfully, it is fundamental that efficiency does not remain constant but improves over time; otherwise, dissipation costs will grow linearly with liquidity, leading the enterprise toward rapid saturation or failure.

It means that the enterprise possesses structural inertia, due to fixed costs and contracts, which prevents it from reacting instantly to high-frequency market fluctuations, filtering out daily noise. However, this characteristic can become lethal during sudden crises if the business time constant is too high, making the organization slow to adapt to new economic scenarios like a rate hike.

Monitoring the second derivative of cash allows observing the acceleration of expenses and not just the current consumption speed. This advanced indicator acts as an early warning signal: if acceleration is negative while revenues remain constant, the business is braking dangerously toward insolvency, allowing management to intervene before the situation becomes irreversible.

Did you find this article helpful? Is there another topic you'd like to see me cover?

Write it in the comments below! I take inspiration directly from your suggestions.