Imagine you own an orchard. Each tree produces fruit, but you have to wait for the harvest season to cash in. What if you could sell a portion of your future harvests today to someone willing to pay immediately? Securitization works in a similar way: it’s a financial technique that allows a bank or a company to transform assets that generate future cash flows, like mortgages or loans, into immediate liquid cash. These receivables are “packaged” and turned into financial securities, ready to be sold to investors on the market.

This process, which originated in the Anglo-Saxon world and is regulated in Italy primarily by Law 130/1999, allows the party selling the receivables (the originator) to obtain immediate liquidity and transfer the risk to those who purchase the new securities. On one hand, it’s a powerful engine for the economy because it frees up capital that banks can use to issue new loans. On the other, as the 2008 financial crisis demonstrated, it hides complexities and risks that are crucial to understand, even for those who aren’t finance experts.

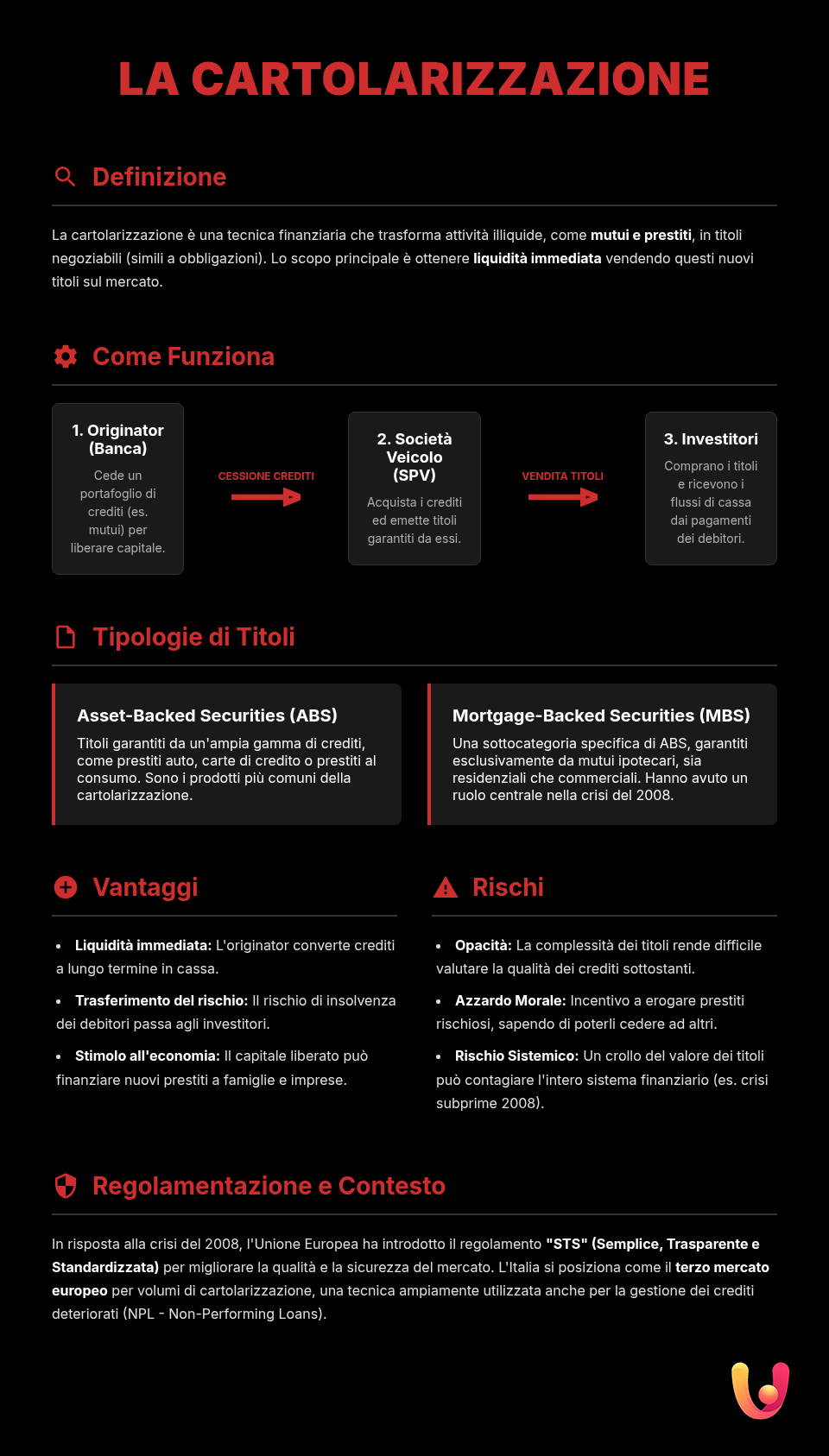

What Is Securitization? The Mechanism Explained

Securitization is a financial operation that transforms receivables that are not easily negotiable, such as a portfolio of mortgages, into financial instruments called “securities.” These securities, similar to bonds, are then sold to investors. The term “securitization” itself comes from this very transformation of debt into tradable “securities.” The entire process allows the original creditor, typically a bank, to unlock its receivables, obtaining immediate liquidity in exchange.

The main function of securitization is to mobilize receivables, which are removed from the creditor’s assets in exchange for immediate liquidity.

There are two main players in this operation. On one side is the Originator, which is the bank or financial institution that issued the original loans (mortgages, consumer loans, etc.) and decides to sell them. On the other side is a Special Purpose Vehicle or SPV, a legal entity created specifically to purchase the receivables. This company is crucial because it isolates the receivables from the originator’s balance sheet, creating a separate pool of assets to secure the investors.

How the Process Works Step by Step

The securitization mechanism, although complex, can be broken down into a few key phases. Each step is designed to ensure that the receivables are transformed into securities in a secure and transparent manner, at least in theory. Let’s see how it works in detail.

- Sale of Receivables: The originator (e.g., a bank) selects a pool of homogeneous receivables, such as a set of residential mortgages or auto loans, and sells them to the Special Purpose Vehicle (SPV). This sale, often on a non-recourse basis (pro-soluto), also transfers the risk of debtor default to the SPV.

- Issuance of Securities: To finance the purchase of the receivables, the SPV issues bond-like securities on the market, known as Asset-Backed Securities (ABS). The value and returns of these securities are directly linked to the cash flows (the payments made by the original debtors) generated by the purchased pool of receivables.

- Market Placement: The ABS are sold to investors, such as pension funds, insurance companies, or other institutional investors. The proceeds from the sale are used by the SPV to pay the originator the price for the sold receivables, thus providing it with immediate liquidity.

- Servicing and Payment: A specialized company, called a Servicer, is responsible for collecting payments from the original debtors. The collected cash flows are then transferred to the investors who purchased the securities, in the form of periodic coupon payments and principal repayment.

ABS and MBS: Two Sides of the Same Coin

Although the basic principle is the same, securitized products are distinguished by the nature of the underlying receivables. The two main categories are Asset-Backed Securities (ABS) and Mortgage-Backed Securities (MBS). Understanding their difference is crucial to grasping the diversity of risk and return they offer. MBS are backed exclusively by mortgages, while ABS are backed by almost any other type of financial asset. Both transform debt into an investment, but they draw from different sources of the real economy.

Asset-Backed Securities (ABS): Beyond Mortgages

Asset-Backed Securities (ABS) are securities backed by a portfolio of various financial assets, excluding mortgages. This category is extremely broad and can include:

- Auto loans: payments made for the purchase of a car.

- Consumer loans: financing for the purchase of goods and services.

- Credit card receivables: debts accumulated by credit card holders.

- Student loans: repayments of loans granted to finance education.

- Trade receivables: invoices that a company has against its customers.

- Auto loans: payments made for the purchase of a car.

- Consumer loans: financing for the purchase of goods and services.

- Credit card receivables: debts accumulated by credit card holders.

- Student loans: repayments of loans granted to finance education.

- Trade receivables: invoices that a company has against its customers.

The diversity of the underlying assets makes ABS a flexible instrument, but it requires careful analysis of the credit quality of each portfolio. Through a process called tranching, the securities are often divided into different “slices” (tranches) with different risk and return profiles to meet the needs of different types of investors.

- Auto loans: payments made for the purchase of a car.

- Consumer loans: financing for the purchase of goods and services.

- Credit card receivables: debts accumulated by credit card holders.

- Student loans: repayments of loans granted to finance education.

- Trade receivables: invoices that a company has against its customers.

The diversity of the underlying assets makes ABS a flexible instrument, but it requires careful analysis of the credit quality of each portfolio. Through a process called tranching, the securities are often divided into different “slices” (tranches) with different risk and return profiles to meet the needs of different types of investors.

Mortgage-Backed Securities (MBS): Mortgages as Collateral

Mortgage-Backed Securities (MBS) are a specific subcategory of ABS, but given their importance, they deserve separate treatment. These securities are backed exclusively by a pool of mortgage loans. In practice, someone who buys an MBS is indirectly financing home purchases and, in return, receives a stream of payments derived from the installments paid by the mortgage borrowers. MBS were among the first securitization instruments to become widespread and still represent a significant portion of the market today.

However, they are also infamous for the central role they played in the 2008 global financial crisis. The problem arose when mortgage pools included a growing number of subprime loans, which are mortgages granted to people with a high risk of default. When interest rates rose, many of these borrowers could no longer afford their payments, causing the value of MBS to collapse and triggering a devastating domino effect throughout the entire global financial system.

Advantages and Disadvantages of Securitization

Like any sophisticated financial instrument, securitization has two faces. On one hand, it offers tangible benefits to banks, businesses, and the economy as a whole; on the other, it hides risks that, if not managed correctly, can have systemic consequences. It is a classic example of financial innovation that balances opportunity and danger, a recurring theme in modern economic culture, where the tradition of prudence clashes with the drive for efficiency.

The Advantages: Liquidity and Risk Transfer

For banks and financial companies (the originators), the main advantage is access to immediate liquidity. Instead of waiting years to collect the installments of a twenty-year mortgage, a bank can sell the loan and immediately obtain fresh capital to use for new activities, such as granting more loans to households and businesses. This not only improves the bank’s balance sheet but also stimulates the real economy. Another crucial benefit is the transfer of credit risk. By selling the receivables, the originator also transfers the risk that debtors will not pay to the investors, thus freeing up regulatory capital and improving its capital adequacy ratios.

The Risks: Complexity and Systemic Crises

The main risk of securitization lies in its complexity and opacity. Overly elaborate financial structures can make it difficult for investors themselves to fully understand the quality of the underlying receivables and the risks they are exposed to. The 2008 crisis taught us that when incentives are misaligned, the system can become fragile. In the originate-to-distribute model, banks might be incentivized to issue low-quality loans, knowing they can quickly transfer the risk elsewhere. This behavior, combined with overly optimistic ratings from rating agencies, created a bubble whose burst demonstrated how the default of thousands of individual mortgage borrowers could trigger a systemic financial crisis.

Securitization in Italy and Europe

The securitization market in Europe has undergone profound transformations since the financial crisis. While in 2010 it was worth about €2 trillion, by the end of 2022 it had shrunk to €540 billion, a sign of greater caution from regulators and investors. The European Union responded by introducing the Securitisation Regulation (EU 2017/2402), which aims to create a more robust and transparent market. This regulation introduced the “STS” (Simple, Transparent, and Standardised) label to certify high-quality securitizations and restore investor confidence.

According to data from the European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA), at the end of 2022, Italy was the third-largest market for securitizations in Europe, accounting for 17% of the total, after France (25%) and Germany (21%). This positions the country as a key player in the continental financial landscape.

In Italy, securitization is used not only to manage performing loans but also to dispose of non-performing loans (NPLs), helping banks clean up their balance sheets. In recent years, there has also been a growth in real estate securitizations, which reached a value of €3.8 billion in 2025, with a 43% increase in dedicated SPVs in a single year. This blend of traditional finance and innovative tools like securitization shows how even in a Mediterranean context, often tied to classic banking models, innovation can find fertile ground to optimize capital management and support the economy. To learn more about how risk is measured in similar contexts, it may be useful to read the practical guide to Value at Risk (VaR).

In Brief (TL;DR)

Securitization is a financial process that transforms debts (like mortgages or loans) into tradable securities, known as Asset-Backed Securities (ABS) and Mortgage-Backed Securities (MBS), to be sold to investors.

We will analyze how debts, including mortgages, are transformed into tradable securities (ABS and MBS), highlighting both the benefits for financial institutions and the potential risks for the entire economic system.

We will explore the advantages of these operations for banks and the potential systemic risks they can trigger.

Conclusions

Securitization is a powerful and ambivalent financial tool. When used with prudence and transparency, it can generate liquidity, distribute risk, and grease the wheels of the economy, transforming illiquid assets like mortgages into investment opportunities and thus financing growth. Instruments like ABS and MBS allow for portfolio diversification and access to returns that would otherwise be difficult to obtain, as explained in our guide to building a modern portfolio. However, its complexity requires clear rules and careful supervision.

The 2008 crisis painfully demonstrated how opacity and moral hazard can turn a useful innovation into a systemic threat. The European response, with the STS regulation, seeks to strike a balance, promoting a healthy market that can support the economy without repeating the excesses of the past. For citizens and small savers, understanding the basic mechanisms of securitization is not just financial literacy, but an essential tool for reading contemporary economic reality and understanding how risks, even those seemingly distant like an American mortgage, can have a global impact. For those who wish to further explore hedging instruments, the guide to Interest Rate Swaps (IRS) offers interesting insights.

Frequently Asked Questions

Imagine a bank has many small loans, like a basket full of oranges. With securitization, the bank ‘packages’ these loans (the oranges) into a large crate and turns them into financial securities to sell to investors. This way, the bank gets immediate cash to make new loans and transfers the risk that the original debtors won’t pay to those who buy the securities.

The difference lies in the type of ‘fruit’ used to fill the crate. MBS (Mortgage-Backed Securities) are securities backed exclusively by a pool of real estate mortgages. ABS (Asset-Backed Securities), on the other hand, are more generic and can be backed by various types of receivables, such as auto loans, consumer loans, or credit card debt.

Mainly for two reasons. First, to get immediate liquidity: instead of waiting years for loans to be repaid, the bank sells the receivables and gets the cash right away, which it can use to grant new financing. Second, to transfer risk: the danger that debtors won’t be able to pay their installments is moved from the bank to the investors who buy the securitized assets.

The biggest risk is ‘credit risk,’ which is the possibility that the original debtors will not pay their debts. If this happens, the cash flows that feed the securities decrease, and the investor can lose part or all of their invested capital. Another risk is related to the complexity of these instruments, which sometimes makes it difficult to correctly assess the quality of the underlying receivables.

Yes, it played a central role. The crisis was triggered by the securitization of large quantities of American ‘subprime’ mortgages, which were loans granted to high-risk individuals. When these debtors stopped paying, the value of the related MBS collapsed, creating a domino effect that overwhelmed the global financial system. The problem was the excessive complexity and poor quality of the packaged receivables.

Did you find this article helpful? Is there another topic you’d like to see me cover?

Write it in the comments below! I take inspiration directly from your suggestions.