It begins with a phone call from an unknown number. You pick up, perhaps out of habit or curiosity. You say, “Hello? Who is this?” There is a brief pause, some static, and then the line goes dead. You think nothing of it—a wrong number, a glitch in the network. But in those fleeting moments, something profound and irreversible has occurred. AI voice cloning, the main entity driving this technological paradigm shift, has just captured enough data to reconstruct your digital vocal identity entirely.

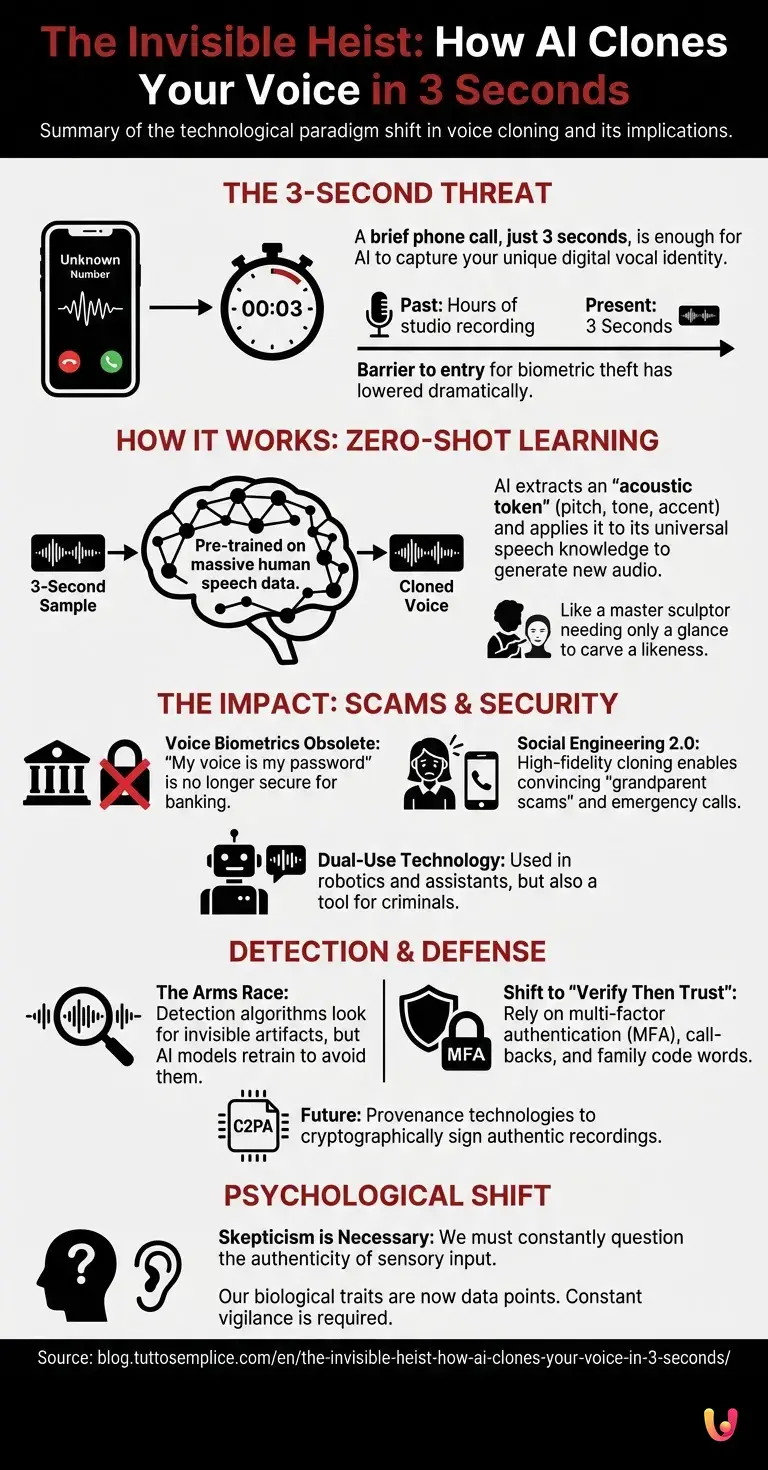

By 2026, the days of needing hours of studio-quality recordings to synthesize a voice are long gone. We have entered an era where the barrier to entry for biometric theft has lowered to a terrifyingly trivial threshold: three seconds. This is not science fiction; it is the culmination of rapid advancements in artificial intelligence and machine learning that have transformed the human voice from a biological signature into a downloadable asset. But how can such a tiny fragment of sound provide enough information to fool banks, family members, and biometric security systems? The answer lies in the sophisticated architecture of modern neural networks and the way they have learned to “hallucinate” reality.

The Architecture of Acoustic Theft

To understand how three seconds is sufficient, we must first understand what the AI is actually doing. In the past, text-to-speech systems relied on “concatenative synthesis.” This involved recording a voice actor reading thousands of sentences, chopping those recordings into tiny phonetic units, and pasting them back together to form new words. It was the audio equivalent of a ransom note made from magazine clippings—functional, but clearly artificial.

Today’s technology, however, relies on Generative AI and neural networks. Instead of pasting together pre-recorded sounds, these models generate raw audio waveforms from scratch. They function similarly to LLMs (Large Language Models) like GPT-4 or its successors. Just as an LLM predicts the next word in a sentence based on probability, a Large Audio Model predicts the next acoustic fraction of a second based on the data it has processed.

The breakthrough that enabled the “three-second” phenomenon is known as “Zero-Shot Learning.” The AI model has already been trained on tens of thousands of hours of human speech from diverse speakers. It understands the physics of how vocal cords vibrate, how the tongue shapes air, and the rhythmic structures of language. It possesses a “universal theory” of human speech. When you provide your three-second sample, you aren’t teaching the AI how to speak; you are simply providing the timbre and prosody—the acoustic texture and rhythm—that it applies to its pre-existing knowledge. It is akin to a master sculptor who knows exactly how to carve a human face and only needs a single glance at a model to capture their specific likeness.

Deconstructing the Three Seconds

What exactly is hidden in those three seconds of audio? To the human ear, it is just a greeting. To a machine learning algorithm, it is a dense data packet containing your unique biometric markers.

When the AI analyzes that brief clip, it extracts an “acoustic token” or a speaker embedding. This is a mathematical representation of your voice’s pitch, tone, resonance, and accent. Because the underlying model is so robust, it can extrapolate how you would sound saying words you never actually spoke in the sample. If the sample contains a question, the AI learns how your pitch rises at the end of a sentence. If it contains a breath, it learns your respiration patterns.

This capability allows for automation on a massive scale. Scammers no longer need to manually splice audio. They can feed a three-second clip into a software interface, type any text they wish, and the system will output a cloned voice that is statistically indistinguishable from the original. This synthesis happens in near real-time, allowing for dynamic interactions that can fool even the most attentive listeners.

The Death of “Voice Is My Password”

For years, banks and service providers touted voice biometrics as the ultimate security measure. “My voice is my password” became a common passphrase for telephone banking. The premise was that the human voice is as unique as a fingerprint. While physically true, the digital replication of that voice has rendered the security concept obsolete.

The implications of high-fidelity cloning extend far beyond financial fraud. We are seeing the rise of “social engineering 2.0.” Imagine receiving a distressed call from a child or a spouse claiming to be in an emergency. The voice is theirs—the panic in their tone, the specific way they pronounce your name, the background noise—it is all perfectly simulated. These “grandparent scams” have evolved from vague impersonations to precise digital puppetry.

Furthermore, this technology is being integrated into robotics and virtual assistants. While the intention is often benign—to give a robot a comforting, familiar voice or to restore the voice of someone who has lost the ability to speak due to illness—the dual-use nature of the technology remains a persistent vulnerability. The same tool that allows a mute patient to speak with their own voice again allows a criminal to bypass a voice-activated smart lock.

The Arms Race: Detection vs. Deception

As the synthesis technology improves, a parallel industry has emerged focused on detection. If the human ear can no longer distinguish between real and synthetic audio, can a computer?

Researchers are currently developing “anti-spoofing” countermeasures. These systems analyze audio for artifacts that are invisible to humans but glaring to machines. For instance, generative audio often lacks certain high-frequency data or contains subtle phase inconsistencies that occur when a neural network stitches acoustic frames together. Additionally, biological speech has natural irregularities—micro-tremors in the vocal cords or irregular breathing patterns—that are often smoothed out by AI models seeking mathematical perfection.

However, this is a cat-and-mouse game. As detection algorithms improve, the generative models are retrained to avoid those specific artifacts. This cycle of automation and counter-automation suggests that relying solely on technical detection may be a losing battle. Instead, society is moving toward “provenance” technologies—digital watermarking standards (like C2PA) that cryptographically sign authentic recordings at the source, verifying that a piece of audio was recorded by a specific device at a specific time and has not been altered.

The Psychological Impact of Synthetic Reality

The existence of this technology forces a psychological shift in how we perceive reality. We are moving from a “trust but verify” society to a “verify then trust” paradigm. The sanctity of the recorded voice, once admissible as undeniable evidence in courtrooms and trusted implicitly in personal communication, has been shattered.

This skepticism is healthy but exhausting. It requires a constant cognitive load to question the authenticity of sensory input. When we can no longer trust our ears, we must rely on secondary verification channels—calling a person back on a known number, using code words with family members, or utilizing multi-factor authentication that does not rely on biometrics. The “three-second” vulnerability serves as a stark reminder that in the age of advanced AI, our biological traits are simply data points waiting to be harvested.

In Brief (TL;DR)

Sophisticated AI now requires only three seconds of audio to permanently capture and replicate your unique vocal identity.

Generative models utilize zero-shot learning to extrapolate complete speech patterns from tiny samples, bypassing the need for studio recordings.

This technological shift renders voice biometrics obsolete while enabling dangerous new forms of fraud and personalized social engineering.

Conclusion

The realization that three seconds of audio is enough to steal an identity is not merely a technical curiosity; it is a fundamental restructuring of privacy in the digital age. The convergence of neural networks, massive datasets, and sophisticated machine learning techniques has unlocked a capability that was once deemed impossible. While this technology holds immense promise for personalized interfaces, entertainment, and accessibility, it demands a rigorous re-evaluation of how we authenticate ourselves and others. As we navigate this new auditory landscape, the most valuable asset we possess may no longer be the uniqueness of our voice, but the skepticism with which we listen.

Frequently Asked Questions

Modern generative AI models utilizing Zero-Shot Learning now require as little as three seconds of audio to create a convincing vocal clone. Unlike older synthesis methods that needed hours of studio recordings, current neural networks can extract a comprehensive acoustic token—including pitch, tone, and accent—from a brief greeting to reconstruct a complete digital identity.

Yes, a brief interaction where you simply say Hello? Who is this? provides enough data for sophisticated algorithms to replicate your voice. Scammers use these short samples to feed Large Audio Models, which can then generate entirely new sentences that sound statistically indistinguishable from you, facilitating social engineering attacks like family emergency scams.

Relying on voice as a password is no longer considered secure because high-fidelity cloning has rendered unique biological audio markers replicable. Since AI can bypass these biometric locks by simulating the user voice perfectly, experts recommend switching to multi-factor authentication methods that do not rely solely on audio verification.

Detecting synthetic audio with the human ear is becoming nearly impossible, so reliance is shifting toward technical countermeasures and behavioral verification. While researchers are developing tools to spot missing high-frequency data or phase inconsistencies, the best personal defense is to verify the caller identity via a secondary channel or use a pre-agreed code word with family members.

Zero-Shot Learning is a machine learning capability that allows an AI model to perform a task without specific prior training on that exact data instance. In voice cloning, it means the AI possesses a universal theory of human speech and only needs a tiny sample of your specific timbre and prosody to apply its general knowledge and synthesize your voice immediately.

Did you find this article helpful? Is there another topic you’d like to see me cover?

Write it in the comments below! I take inspiration directly from your suggestions.