When you unlock your smartphone to query a chatbot or generate an image, the process feels ethereal. It is a transaction of light and logic, seemingly divorced from the physical constraints of the material world. We have been trained to understand the digital realm in terms of electricity—measured in kilowatt-hours and battery percentages. However, there is a heavier, wetter reality anchoring the cloud to the earth. The main entity sustaining the explosive growth of artificial intelligence is not just silicon or electricity, but water. While you type, a silent torrent is flowing through the infrastructure of the internet, cooling the feverish heat of digital cognition.

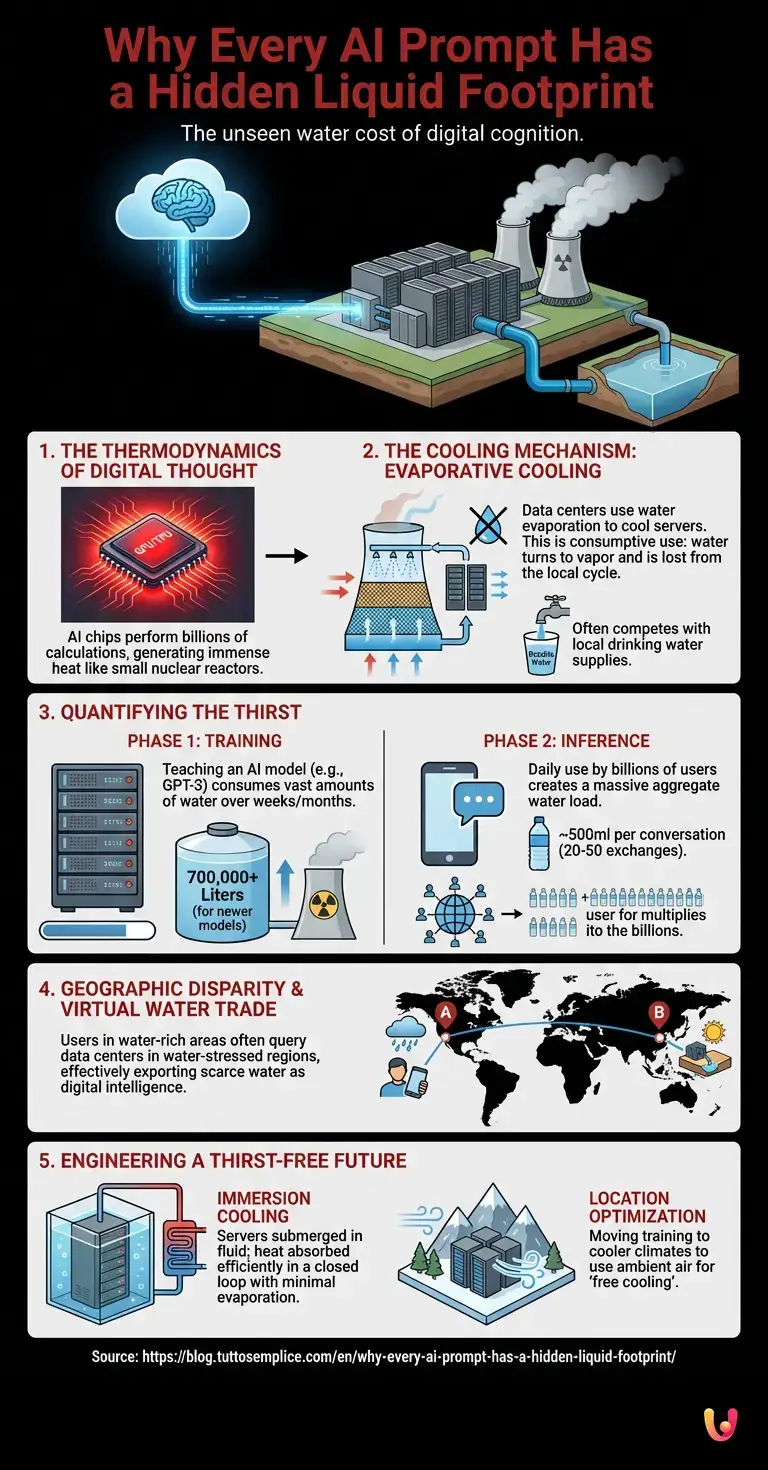

The Thermodynamics of Digital Thought

To understand why your digital interactions have a liquid footprint, one must look inside the data centers that house the brains of modern automation. These facilities are cathedrals of computation, packed with rows of servers containing Graphics Processing Units (GPUs) and Tensor Processing Units (TPUs). These chips are the engines of machine learning, performing the billions of matrix multiplications required to process a single prompt.

Physics dictates that this computation comes with a cost: heat. As electricity courses through the microscopic transistors of a processor, resistance generates thermal energy. When you scale this up to a facility running hundreds of thousands of chips simultaneously to train massive neural networks, the heat output is comparable to that of a small nuclear reactor. If this heat is not removed immediately, the delicate silicon will melt, and the hardware will fail.

This is where the invisible resource comes into play. While air conditioning (using electricity) can cool these servers, it is often inefficient for high-density computing. Instead, data centers rely on evaporative cooling. By exposing hot air to water, the water evaporates, absorbing heat in the process and chilling the air that is then recirculated to the servers. It is an elegant thermodynamic solution, but it is a thirsty one. The water used in this process is often evaporated into the atmosphere, lost forever from the local watershed.

Quantifying the Thirst: From Training to Inference

The consumption of this resource occurs in two distinct phases of an AI model’s lifecycle: training and inference. The numbers are staggering and help bridge the curiosity gap regarding exactly how much “fuel” these systems require.

The Training Phase: Before an AI can answer your questions, it must be taught. Training a major LLM (Large Language Model) like those developed by OpenAI, Google, or Anthropic involves processing petabytes of text data over weeks or months. Research indicates that training a legacy model like GPT-3 consumed roughly 700,000 liters of fresh water—enough to fill a nuclear reactor’s cooling tower. In the context of 2026, where models have grown exponentially larger, this figure has multiplied. This water is used solely to keep the supercomputers at operational temperatures during the intense “learning” period.

The Inference Phase: This is the “daily habit” mentioned in our theme. Inference is what happens when you actually use the AI. Every time you ask a question, the model runs calculations to predict the next token in the sequence. While a single query generates a negligible amount of heat, the aggregate of billions of daily users creates a massive thermal load.

Estimates suggest that a conversation with a standard chatbot—comprising roughly 20 to 50 exchanges—consumes approximately 500 milliliters of water. That is a standard single-use plastic bottle of water “drunk” by the data center for every extended interaction you have. When you consider the global scale of robotics integration and automated customer service agents running 24/7, the gallons consumed shift from the millions to the billions annually.

The Mechanism: How the Cloud Sweats

How does this work mechanically? Most hyperscale data centers utilize cooling towers. These are industrial structures where warm water from the data center is sprayed over a fill material. As air flows through the tower, a portion of the water evaporates, cooling the remaining water, which is then pumped back to heat exchangers to absorb more heat from the servers.

This process is known as “consumptive use.” Unlike water used in a home, which goes down the drain, is treated, and returned to the river, the water in a cooling tower turns into vapor and drifts away. It is removed from the local cycle.

Furthermore, the quality of this water matters. You cannot simply pump seawater into these delicate systems without risking corrosion and bacterial growth (such as Legionella). Therefore, data centers often compete for the same potable (drinkable) water supplies used by local residents and farmers. In regions facing drought, the tension between the thirst of artificial intelligence and the thirst of the population becomes a critical geopolitical issue.

The Geographic Disparity of Data

A secret behind the environmental impact of machine learning is that the user is rarely located where the water is consumed. You might be sitting in a rainy city like Seattle or London, but your query might be routed to a data center in a water-stressed region like Arizona, Spain, or Chile. The routing depends on server load and latency, not environmental impact.

This creates a phenomenon of “virtual water trade,” where arid regions effectively export their scarce water resources to the rest of the world in the form of digital intelligence. As automation becomes more embedded in global supply chains, this invisible export grows. Tech giants have recognized this vulnerability and are pledging to become “water positive”—replenishing more water than they consume—but the physics of cooling high-performance chips remains a stubborn hurdle.

Engineering a Thirst-Free Future

What happens if we run out of water to cool these minds? The industry is racing toward solutions that reduce reliance on evaporative cooling. The future of robotics and AI hardware may lie in “direct-to-chip” liquid cooling or immersion cooling.

Immersion Cooling: In this sci-fi-esque scenario, servers are submerged entirely in a bath of dielectric fluid (a liquid that does not conduct electricity). This fluid absorbs heat far more efficiently than air, and because it circulates in a closed loop, very little is lost to evaporation. This method allows for much higher density neural networks without the accompanying water bill.

Location Optimization: Another strategy involves moving the “training” phase of AI—which is less time-sensitive than the “inference” phase—to data centers located in cooler climates (like the Nordics) where ambient air can cool the servers without evaporating water. This is known as “free cooling.” However, for real-time interactions, servers still need to be close to users to prevent lag, meaning the water consumption for daily use is harder to displace.

In Brief (TL;DR)

Behind every digital prompt lies a physical reality where massive data centers consume torrents of water to cool overheating processors.

Water consumption spikes during both model training and daily inference, with a single short chat costing approximately a bottle of water.

This evaporative cooling process permanently removes potable water from local cycles, intensifying resource competition in communities facing environmental drought.

Conclusion

As we navigate the year 2026, the integration of artificial intelligence into our lives is undeniable. It drives our cars, writes our code, and manages our schedules. Yet, this digital magic relies on a very analog resource. The invisible resource your daily tech habit is consuming by the gallon is fresh water. Recognizing this connection bridges the gap between the virtual and the physical, reminding us that every byte of data has a biological cost. As we marvel at the capabilities of LLMs and the speed of automation, we must also advocate for the sustainable engineering that will ensure our digital future does not drink our physical future dry.

Frequently Asked Questions

Estimates suggest that a standard conversation with an AI chatbot, comprising roughly 20 to 50 exchanges, consumes approximately 500 milliliters of water. This consumption is driven by the massive thermal load generated by data center processors during the inference phase, which requires extensive evaporative cooling to prevent hardware overheating.

While air conditioning is used, it is often inefficient for the high-density computing required by modern AI chips like GPUs and TPUs. Data centers rely on evaporative cooling because it is a thermodynamically elegant solution where water absorbs heat as it turns into vapor. However, this method is considered consumptive use because the water evaporates into the atmosphere rather than returning to the local water cycle.

Training is the initial, intense learning period where a model processes petabytes of data, consuming hundreds of thousands of liters of water to cool supercomputers over weeks. Inference is the daily operational phase where the AI answers user queries; while individual queries generate less heat, the aggregate volume of billions of global interactions creates a continuous and massive water demand that rivals or exceeds the training phase.

There is often a geographic disconnect between the user and the server, leading to a phenomenon called virtual water trade. A user in a water-rich city might have their digital query routed to a data center in a water-stressed region like Arizona or Spain. This means arid regions are effectively exporting their scarce potable water resources to power global digital services.

To mitigate water consumption, the industry is moving toward immersion cooling, where servers are submerged in a dielectric fluid that absorbs heat in a closed loop without evaporation. Additionally, companies are looking at location optimization, which involves moving the training phase of AI models to cooler climates, such as the Nordics, to utilize ambient air for free cooling instead of relying on water evaporation.

Sources and Further Reading

Did you find this article helpful? Is there another topic you’d like to see me cover?

Write it in the comments below! I take inspiration directly from your suggestions.