In Brief (TL;DR)

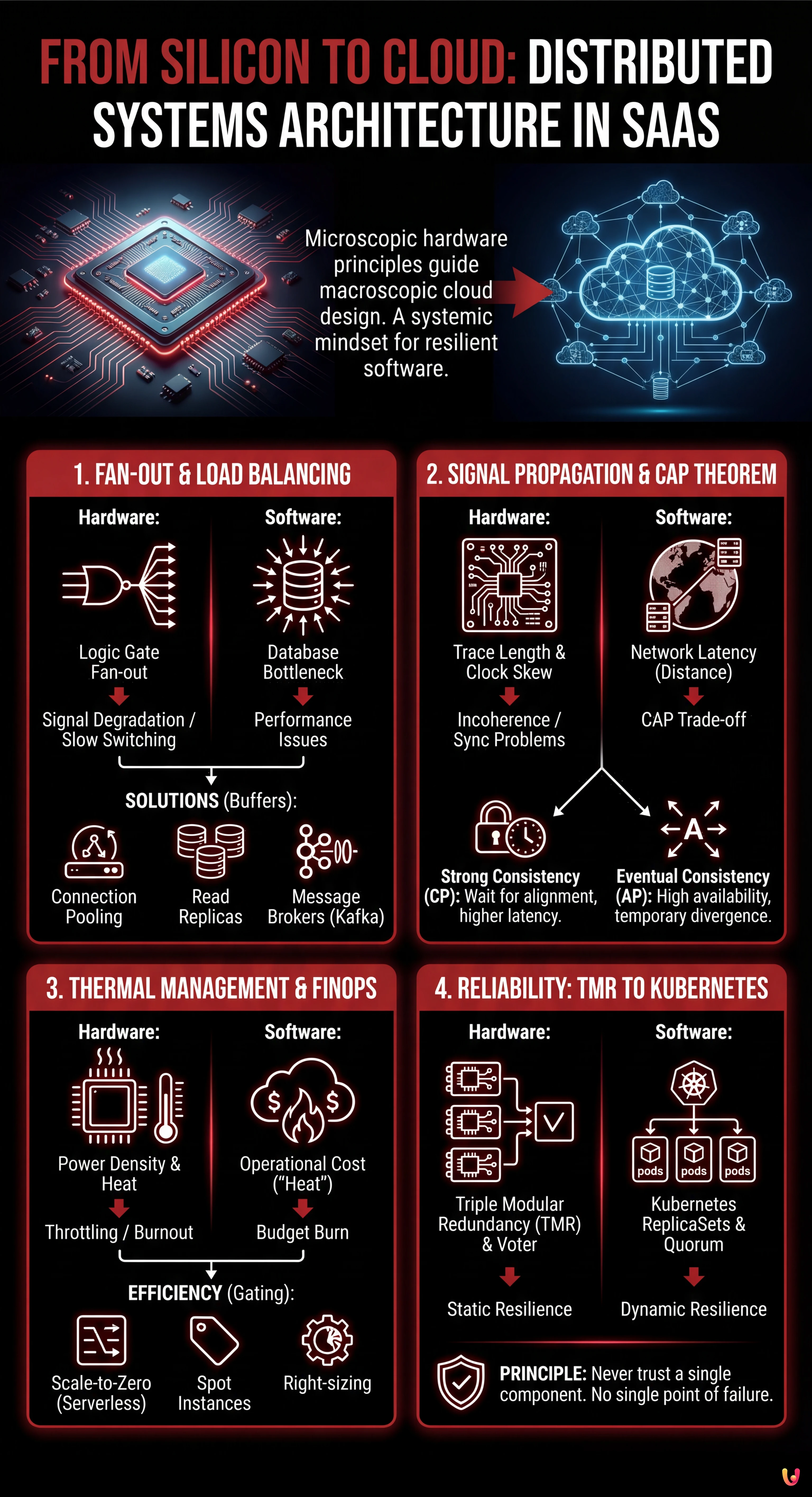

Distributed systems architecture in the cloud reflects on a macroscopic scale the fundamental physical laws governing integrated circuit design.

Hardware constraints like Fan-out and signal propagation perfectly explain modern challenges of load balancing and data consistency.

Processor thermal optimization finds its equivalent in FinOps, transforming silicon energy management into strategies to reduce cloud costs.

The devil is in the details. 👇 Keep reading to discover the critical steps and practical tips to avoid mistakes.

It is 2026, and while generative artificial intelligence has rewritten the rules of human-machine interaction, the fundamental laws of physics and logic remain unchanged. For those who, like me, began their careers with a soldering iron in hand and an integrated circuit (IC) schematic on the table, the current Cloud Computing landscape does not appear as an alien world, but as a macroscopic evolution of problems we have already solved on a microscopic scale. At the center of it all is distributed systems architecture: a concept we apply today to global clusters, but which originates from the interconnections between transistors on a silicon wafer.

In this technical essay, we will explore how the systemic mindset required to design reliable hardware is the keystone for building resilient software. We will analyze how the physical constraints of silicon find their perfect analogues in the immaterial challenges of modern SaaS.

1. The Fan-out Problem: From Logic Gates to Load Balancing

In electronic engineering, Fan-out defines the maximum number of logic inputs an output can reliably drive. If a logic gate attempts to send a signal to too many other gates, the current splits excessively, the signal degrades, and switching (0 to 1 or vice versa) becomes slow or undefined. It is a physical limit of driving capability.

The Software Analogue: The Database Bottleneck

In distributed systems architecture, the concept of Fan-out manifests brutally when a single service (e.g., a master database or an authentication service) is bombarded by too many concurrent requests from client microservices. Just as a transistor cannot supply infinite current, a database does not have infinite TCP connections or CPU cycles.

The hardware solution is the insertion of buffers to regenerate the signal and increase driving capability. In SaaS, we apply the same principle through:

- Connection Pooling: Acting as a current buffer, keeping connections active and reusable.

- Read Replicas: Parallelizing the read load, similar to adding amplification stages in parallel.

- Message Brokers (Kafka/RabbitMQ): Decoupling the producer from the consumer, handling load spikes (backpressure) exactly as a decoupling capacitor stabilizes voltage during absorption peaks.

2. Signal Propagation: Clock Skew and CAP Theorem

On high-frequency circuits, the speed of light (or rather, the signal propagation speed in copper/gold) is a tangible constraint. If a trace on the PCB is longer than another, the signal arrives late, causing synchronization problems known as Clock Skew. The system becomes incoherent because different parts of the chip see the “reality” at different times.

The Tyranny of Distance in the Cloud

In the cloud, network latency is the new propagation delay. When designing a geo-redundant distributed systems architecture, we cannot ignore that light takes time to travel from Frankfurt to Northern Virginia. This physical delay is the root of the CAP Theorem (Consistency, Availability, Partition tolerance).

An electronic engineer knows they cannot have a perfectly synchronous signal on a huge chip without slowing down the clock (sacrificing performance for coherence). Similarly, a software architect must choose between:

- Strong Consistency (CP): Waiting for all nodes to align (like a slow global clock), accepting high latency.

- Eventual Consistency (AP): Allowing nodes to diverge temporarily to maintain high availability and low latency, handling conflicts retroactively (similar to asynchronous or self-timed circuits).

3. Thermal Management vs. FinOps: Efficiency as a Constraint

Power density is enemy number one in modern processors. If heat is not dissipated, the chip goes into thermal throttling (slows down) or burns out. Modern VLSI (Very Large Scale Integration) design revolves around the concept of “Dark Silicon”: we cannot turn on all transistors simultaneously because the chip would melt. We must turn on only what is needed, when it is needed.

Cost is the Heat of the Cloud

In the SaaS model, the “heat” is the operating cost. An inefficient architecture doesn’t melt servers (the cloud provider handles that), but it burns the company budget. FinOps is modern thermal management.

Just as a hardware engineer uses Clock Gating to turn off unused parts of the chip, a Cloud Architect must implement:

- Scale-to-Zero: Using Serverless technologies (like AWS Lambda or Google Cloud Run) to completely shut down resources when there is no traffic.

- Spot Instances: Leveraging excess capacity at low cost, accepting the risk of interruption, similar to using components with wider tolerances in non-critical circuits.

- Right-sizing: Adapting resources to the actual load, avoiding over-provisioning which in the hardware world would equate to using a 1kg heatsink for a 5W chip.

4. Reliability: From TMR to Kubernetes Clusters

In avionics or space systems, where repair is impossible and radiation can randomly flip a bit (Single Event Upset), Triple Modular Redundancy (TMR) is used. Three identical circuits perform the same calculation and a voting circuit (voter) decides the output based on the majority. If one fails, the system continues to function.

The Orchestration of Resilience

This is the exact essence of a Kubernetes cluster or a distributed database with Raft/Paxos consensus. In a modern distributed systems architecture:

- ReplicaSets: Maintain multiple copies (Pods) of the same service. If a node falls (hardware failure), the Control Plane (the “voter”) notices and reschedules the pod elsewhere.

- Quorum in Databases: To confirm a write in a cluster (e.g., Cassandra or etcd), we require that the majority of nodes (N/2 + 1) confirm the operation. This is mathematically identical to the voting logic of hardware TMR.

The substantial difference is that in hardware, redundancy is static (hardwired), while in software it is dynamic and reconfigurable. However, the basic principle remains: never trust the single component.

Conclusions: The Unified Systemic Approach

Moving from silicon to cloud does not mean changing professions, but changing scale. Designing an effective distributed systems architecture requires the same discipline needed for the tape-out of a microprocessor:

- Understand physical constraints (bandwidth, latency, cost/heat).

- Design for failure (the component will break, the packet will be lost).

- Decouple systems to prevent error propagation.

In 2026, tools have become incredibly abstract. We write YAML describing ephemeral infrastructures. But beneath those layers of abstraction, there are still electrons running, clocks ticking, and buffers filling up. Maintaining awareness of this physical reality is what distinguishes a good developer from a true Systems Architect.

Frequently Asked Questions

Cloud architecture is considered a macroscopic evolution of the microscopic challenges typical of integrated circuits. Physical problems like heat management and signal propagation in silicon find a direct correspondence in software cost management and network latency, requiring a similar systemic mindset to ensure resilience and operational efficiency.

Fan-out in software manifests when a single service, such as a master database, receives an excessive number of concurrent requests, analogous to a logic gate driving too many inputs. To mitigate this bottleneck, solutions like connection pooling, read replicas, and message brokers are adopted, acting as buffers to stabilize the load and prevent performance degradation.

Network latency, comparable to signal propagation delay in electronic circuits, prevents instant synchronization between geographically distant nodes. This physical constraint forces software architects to choose between Strong Consistency, accepting higher latencies to wait for node alignment, or Eventual Consistency, which prioritizes availability by tolerating temporary data misalignments.

In the SaaS model, operating cost represents the equivalent of heat generated in processors: both are limiting factors that must be controlled. FinOps strategies like «Scale-to-Zero» and «Right-sizing» mirror hardware techniques like «Clock Gating», turning off or resizing unused resources to optimize efficiency and prevent the budget from being consumed unnecessarily.

Kubernetes clusters dynamically apply the principles of Triple Modular Redundancy used in critical hardware systems. Through the use of ReplicaSets and consensus algorithms for distributed databases, the system constantly monitors service status and replaces failed nodes based on voting and majority mechanisms, ensuring operational continuity without single points of failure.

Did you find this article helpful? Is there another topic you'd like to see me cover?

Write it in the comments below! I take inspiration directly from your suggestions.